1. [top] Deceiving the eye with ‘trompe l’oeil’ — a painting of papers and tools held by

straps, by the Dutch painter Evert Collier (c. 1640–1708). 2. [bottom left] Perspectival

illusion in the Galleria degli Antichi, Sabbioneta, 1582–1587. 3. [bottom right]

Gable wall, unidentified building in northern Italy.

The term ‘trompe l’oeil’ (or trompe–l’oeil with a hyphen, as in the original French) indicates an intention to deceive the eye either by the realistic depiction in paint of three–dimensional objects in two dimensions on a flat surface or canvas, sometimes using tricks of perspective, always exploring the boundaries between fantasy and reality. The size of the ‘canvas’ is immaterial — it can be small scale [1] or it can cover a whole wall [2], or even the side of a building [3]. There may be little attempt made to achieve realism [4] as in this formalised representation of windows on a blank gable end; or conversely a giant full–size photograph may be used to screen restoration work on a building [5], in this case the cathedral at Verona — from a distance this can be very deceptive. In these instances the windows in question should perhaps be classified as mural art because they lie in the same plane as the wall, as opposed to the more common type of false window that sits in a recessed window aperture.

4. [left] Gable wall of studios in Hammersmith, west London. 5. [right] Full size photograph

of Verona Cathedral mounted on scaffolding in front of Verona Cathedral. Only the sections

representing sky give it away.

In many continental examples a rudimentary recognition of the value of trompe l’oeil perspective is seen in the form of false windows showing casements partially open (always inward) [6, 7, 8]. Examples such as these abound throughout the towns and cities of Italy. Occasionally, painted window shutters are seen which are almost indistinguishable from the real thing [9]. Such is the skill and artistic ambition of Italian painters that apparently three–dimensional architraves may be added to real windows, together with trompe l’oeil pilasters and other realistic–looking enrichments [10]. A minor tour–de–force such as this example [11] is by no means exceptional: even after close study we are left asking ourselves ‘which of the two windows is real and which false’? Mediterranean countries have a long and enviable artistic tradition in many fields not the least of which is that of trompe l’oeil painting so it is almost comforting to find an Italian example [12] in which an attempt to deceive has fallen flat on its face.

6, 7, 8, [top row] A selection of false windows from Rome. 9. [middle left] In this example,

also from Rome, the shutters either side of the central window are painted onto a blank plastered

surface. 10. [middle right] An example in which the shutters and windows are real, but the

window surrounds, piers, and string courses are all painted onto the wall. 11. [bottom left]

A pair of casements protected by iron grilles (private villa in northern Italy). Which one is real

and which trompe l’oeil? 12. [bottom right] A failed attempt,presumably the result of the

insertion of a new floor: Tinitá dei Monte, Rome

‘Fancy’ derives directly from ‘fantasy’, which in turn is from Latin and Greek ‘fantasia’, a word that has gathered around itself a number of meanings or interpretations, but which originally meant ‘to show’, ‘to make visible’, to make joyful use of the faculty of imagination.

FALSE WINDOWS: FANCY — The Knaresborough Town Windows Project

Public Art with a Purpose . . . and a Sense of Humour

Visitors to the historic Yorkshire town of Knaresborough may be surprised to encounter a collection of public works of art in the form of lively trompe l’oeil paintings set into the recesses of the blind windows of the older buildings, illustrating themes based on local history and the town’s rich heritage [13, 14, 15]. What are they doing there and why are there so many so many? We are used to seeing murals and artworks of a similar kind throughout continental towns and cities, but relatively rarely in the UK. So where has this effusion of positively Mediterranean playfulness and exuberance come from? For the answer we have to look back to 1996, when a local extrovert and part–time folk–singing pub entertainer proposed and masterminded, with his son, the first Knaresborough Festival. This ran for five years, at which point a new group of volunteers joined the organisation and the event was renamed the Knaresborough Festival of Entertainment and Visual Arts (FEVA). Ten years later the event has become a fully–fledged festival, led by a not–for–profit organisation run by the community for the community, obtaining funding from commercial sponsors together with a variety of public sources. Now the ten–day event attracts visitors and provides a welcome boost for local businesses. Meanwhile, and in parallel, local and regional agencies have become involved in the festival, largely providing matching funding and therefore controlling the direction in which the event has been able to develop; in view of the unusual nature of what has become known as the Town Windows Project it is surprising that it happened at all.

The rather Byzantine process worked something like this: Yorkshire Forward, a regional development agency charged with improving the Yorkshire and Humberside economy, funded by central government and the European Regional Development Fund, identified a number of market towns in need of help, amongst them Knaresborough. This they implemented through an offshoot agency, Renaissance Market Towns, which later merged with the already existing Knaresborough Regeneration Partnership to become ‘Renaissance Knaresborough’ — the remit of which was to develop ideas beneficial to the local area and to encourage and provide support for a variety of businesses and other undertakings, amongst them FEVA, which is run by a small committee and a group of volunteers. This is where the ideas come from, and where the Town Windows Project was born — the concept of filling blank windows in the town with three–dimensional paintings representing ‘real’ windows with local and historical figures within. From that point on — sometime in the early 2000s — the team’s effort revolved around budgeting and obtaining funds for the first phase, commissioning artists (local if possible), identifying suitable sites, and organising permissions and installation.

The actual cost turned out to be around £1000 a window, funded by Knaresborough Town Council; Harrogate Borough Council, who covered the planning application costs, and the Arts Council, who imposed an open tendering condition. Renaissance Knaresborough sent a brief to Arts Connection, a network of artists in North Yorkshire, who in turn received responses from seven artists, three of whom were Knaresborough–based. Finding owners who were willing to have the artworks displayed on the premises took time. There were objections at an early stage from a few local architectural purists, who felt that the artworks compromised the integrity of the historic fabric of the town, though this was successfully countered by pointing out that they were non–destructive and reversible, and were intended only to last for the duration of the festival. (In reality the scheme was so successful with residents and visitors that most are still in position today, with more planned for future festivals). Once the sites were chosen roads were closed and a cherry–picker hired to place the panels in position, the work being done on Sundays to avoid traffic congestion. To reduce hire costs it was decided to allot two panels per building where possible, which is why most of the trompe l’oeil window panels are mounted in pairs. Public liability insurance was taken out to cover the possibility of damage to members of the public in the unlikely case of failure of any of the fixings.

Local Subjects

The panels are intended to remind the townspeople of aspects of their history that they might otherwise have forgotten, and to tell visitors of the interesting characters and events from Knaresborough’s distant and recent past; printed information sheets are available to the public from locations within the town, explaining the significance of each of the panels.

18. [left] Mother Shipton gazes out from the top floor of The Market Tavern. 19. [centre]

The artist has painted herself twice in this view. 20. [right] King John, distributing Maundy

money to the poor of Knaresborough.

Zoo (16 — 18 High Street)

A humorously surreal evocation [16] by the artist Julie Cope of the Knaresborough Zoological Gardens that formerly existed at Conyngham Hall on the outskirts of the town. Started in 1965 by a former circus ringmaster and one–time pet shop owner, the zoo had a short but eventful life and diverted local residents with a string of amusing but potentially dangerous calamities. Amongst these was the theft, in 1983, of three valuable pythons, and the accidental electrocution of Ronnie the rhinoceros due to a freak accident. The zoo owner had a Sumatran tiger that he walked round the town on a leash. Cassius, the largest female reticulated python in captivity, made it into the Guinness Book of Records, at 27 feet long; as also did Simba the Lion (at 826 lb., the heaviest lion in captivity at that time) whose other claim to fame was that he had starred alongside Elizabeth Taylor in the 1963 film version of Cleopatra. Amidst debts and other animal health–related problems the Zoo was forced to close in the mid 1980s, when the council refused to renew the zoo’s licence on the grounds of inadequate hygiene and enclosure provision. In spite of this many of the older residents claim to remember Knaresborough Zoo with affection. History does not relate whether a giraffe and a zebra were ever part of the animal community.

Mother Shipton (Market Tavern, Castlegate)

Traditionally portrayed as a hideously ugly old crone, Mother Shipton, the renowned prophetess [17, 18]. appears here as a sweet old lady perched somewhat precariously on the cill of a second floor window, with her cat and her legendary book of prophesies, and a string of objects above her head representing articles ‘turned to stone’ in the calcifying limestone–rich waters of the Dropping Well with which she is associated.

It has been said of her ill–favoured appearance that she can be considered the forerunner of the pantomime dame and the model for Mr Punch, and it is certainly the case that she was the subject of books and plays from middle of the seventeenth century onwards. There is a connection between the hook–nosed Pulcinella character in the Italian Commedia dell’Arte and the marionette/puppet Punch; it seems likely that Mother Shipton would have been drawn into this field in plays such as ‘Harlequin and Mother Shipton’ (1826) by the conflation of the two characters because of their supposed physical likeness.

Born around 1488 in Knaresborough in a cave now known as Mother Shipton’s cave, she became known for her prophetic utterings and eventually gained the titles ‘The Yorkshire Sybil’ and England’s Nostradamus. Her deformity, if early illustrations are to be relied upon, is considered to be due to a form of acromegaly, an exaggerated distortion of the facial features, tending toward a witch–like appearance. After her death her prophesies were published as rhyming couplets; these were naturally couched in a form of language which allowed a wide number of interpretations. At least fifty editions of books or pamphlets have appeared since 1641 containing Mother Shipton’s verses, some of which have turned out to be Victorian fakes — such as the one that predicted ‘The world to an end shall come, In eighteen hundred and eighty one’. She was also credited with making predictions that she didn’t make, such was the gullibility of the world; Samuel Pepys records in his diary that when in 1666 the news that London was on fire was brought to Prince Rupert, then on board ship at Portsmouth, his reaction was ‘now Shipton’s prophesy is out’. She had in fact vaguely forecast the destruction of London from some unknown cause, and event for which we are still waiting.

Artist in Residence (4 Castlegate)

As a contrast to the heritage themes that make up most of the Town Windows, the artist Julie Cope has portrayed herself relaxing at a second floor window with her cat, and again perched precariously on the outside of a first floor window [15, 19]. Close inspection reveals that in this she is seemingly over–painting the blank brickwork of the blind window, and that in order to maintain a straight line in depicting the right–hand jamb of the window there is also apparently a suitably positioned length of painter’s masking tape temporarily in place — which is not there in fact, just painted on like everything else — a witty piece of trompe l’oeil worthy of our notice.

Alms for the Poor (1 Castlegate)

King John of England (1166 2016) was by all accounts something of a failure as a king, an able administrator but not trusting others or trusted by them. He was also known as John Lackland on account of his failure to regain lands he owned in northern France following a disastrous military campaign. He has given us Magna Carta, which he was forced to sign against his will; this limited the power of kings ever after and has given you and I rights we might not otherwise have enjoyed. The most important clause of this document has given us ‘habeas corpus’, the principle that no–one shall be imprisoned except by due process of law. He had a difference of opinion with the Pope, which might have led to England becoming a protestant country earlier than it actually did, but he patched it up in 1213. Because of his negative qualities (spitefulness and cruelty) he became a recurring character in popular culture, mostly as a villain in stories and films about Robin Hood. John’s involvement in Knaresborough centres around the use of Knaresborough Castle as a centre for government and judicial administration, which continued long after its military significance had diminished. At one point he took over the castle and used it for the collection of revenues associated with rents, harvests, and court proceedings, but was also responsible for strengthening and maintaining the fabric in good condition so that he could use it as a base for hunting in the Forest of Knaresborough.

His portrait here [14, 20] shows a benign countenance and the artist has probably referred to the many contemporary depictions of the king, the most notable being his tomb in Worcester Cathedral, which the facial features in the painting resemble closely. He is seen standing at a first floor window holding what we may take to be Magna Carta in the left hand and distributing Royal Maundy money with the right. This distribution of gifts to the poor first took place in Knaresborough on 5th April 1210. The artist has used a little licence in showing a pair of folding casements opening inwards, as on the continent of Europe, with a view to confining his picture within the jambs of the blind window.

21. [left] Blind Jack of Knaresborough plays his fiddle at Blind Jack’s tavern.

22. [right] Memories of the Civil War.

Blind Jack of Knaresborough (Market Place)

Otherwise known as John Metcalf, civil engineer; born in the town in 1707, Metcalf led an extraordinary life, even for those times. Losing his sight at the age of six due to smallpox, he developed an aptitude for the fiddle and made this his livelihood in his early years. It is said that he took up swimming and diving in spite of his disability, played cards (we may wonder how this worked), rode, and hunted. During the Second Jacobite rebellion of 1745 his connections enabled him to become a recruiting sergeant, raising troops for the king in the Knaresborough area. A spell in the army in Scotland led to him importing Aberdeen stockings into England. Although blind he had started a line as a carrier of people, fish, and stone, which eventually culminated in the creation of a stagecoach line in 1754, for which he drove the coach himself. When, in 1765, Turnpike Trusts were formed to create toll roads Metcalf won a contract to build a three–mile length of road in the Harrogate area, carrying out the surveying work himself, we are told; by the end of his road–building career he had built a total of 180 miles of road. Like Mother Shipton, his memory is preserved in one of the town’s public houses [21].

Civil War (53 Kirkgate)

Like all communities throughout England at the time of the Civil War, in the middle of the seventeenth century, Knaresborough was a town divided within itself. The castle was held by Royalists for a time but came under siege in 1644 following the Battle of Marston Moor, and thereafter fell to the Parliamentarians when one of Cromwell’s cannon successfully breached the curtain wall. An Act of Parliament ensured that the castle was later substantially demolished so that it could have no further military use. In these panels [22], however, the Royalists seem to have the upper hand, with the Cavalier in the upper window about to discharge his musket at short range into the helmeted head of the unsuspecting Roundhead below.

Local Hero (5 Gracious Street)

Squadron Leader James ‘Ginger’ Lacey DFM & Bar [23], a product of Knaresborough’s King James Grammar School, was the second highest scoring British RAF pilot in the Battle of Britain, being credited with the destruction of 28 enemy aircraft and with shooting down or disabling 14 others.

Gunpowder Plot (5–7 Briggate)

Guy Fawkes (1570–1606) although born in York, a distance of twenty miles from Knaresborough, spent much his youth in the district and so is considered a local notable [24]. Brought up in the Protestant faith, he later converted to Catholicism and thereafter spent much of the rest of his life devising ways in which to ensure a return to the Catholic England of Henry the Eighth’s early years. By way of trying to prevent a Protestant king from coming to the throne he conspired with others in 1605 to assassinate King James and members of the House of Lords at the Royal opening of Parliament, an endeavour in which they were all strikingly unsuccessful. Fawkes was discovered in an under–croft below the House of Lords guarding the barrels of gunpowder the night before the event and it is for this reason that he most particularly associated with the Gunpowder Plot, but for their involvement all the plotters were hanged and quartered and, it is said, the body parts distributed and put on public display as a warning to others. J.A. Sharpe in Remember, Remember: A Cultural History of Guy Fawkes Day has expressed the opinion that Guy Fawkes was ‘the only man ever to enter Parliament with honest intentions’.

FALSE WINDOWS: FANCY — A PARISIAN EXCURSION

‘Fenêtres Imaginaires’

25. [left] Rue Quincampoix and the apartment block with false windows visible at the right hand

end, facing the square. 26. [right] Close–up of the false windows. The yellow arrow indicates

the location of the wall plaque [30].

Visitors to the Pompidou Centre, located in the Beaubourg district at heart of Paris, will notice in the nearby Rue Quincampoix an apartment block facing onto a small tree–filled square [25]. The apartment at the right–hand end seems at first sight to be identical with the rest of the block, but on closer inspection is seen to have blind openings with false windows corresponding with the adjacent fenestration. Onto the blind openings are painted matching inward–opening full height casements, protected in each case by painted ornamental metal balconies; in addition the imaginary rooms on the first floor level are protected from the sun by striped fabric blinds painted on the flat surface [26]. Some of the ‘windows’ are depicted as being open, most with the ‘curtains’ drawn back, and many with figures engaged in everyday human activities — a grey–haired man plays a violin [27], while a young woman in contemplative mood watches him in the adjacent window [28]; perhaps we are meant to understand that they are in the same room. On an upper floor a small girl perches dangerously near the cill and surveys the scene outside, while her brother is about to lose his ball through the window [29].

27, 28, 29. Detail of the windows. Note the safety rails at cill level; also the inevitable problems

with curtains caused by the inward–opening casements.

Many foreign visitors have left mystified, and some have recorded their bemusement on internet web sites. So what is the explanation for this charming piece of French whimsicality? There is a clue at ground floor level — a blank wall where normally one would expect to see a shop front or apartment block entrance — and on this wall a small plaque [30], which for those unfamiliar with French might take to be a warning notice of some sort. Even the French themselves might be puzzled by the strange word SEMAH. In order to fully understand this sign we need to go back in time to the early 1960s, when proposals were conceived for the relocation of the nearby wholesale food market ‘Les Halles’ (known traditionally as ‘the belly of Paris’), potentially creating a vacuum in the heart of the city. Thus the opportunity arose to carry out a scheme of comprehensive redevelopment and renewal of 35 hectares (86 acres) of land in the Beaubourg area, for which purpose a company was formed — La Société d’Economie Mixte d’Aménagemant des Halles, ‘SEMAH’, which translates roughly as the Halles Joint Economic Development Company. This massive project, finally opened in 1979, included the vast semi–subterranean shopping plaza, the Forum des Halles; new commercial and residential buildings; a network of new express underground railway lines; and a system of new road tunnels crossing the area [31], joining up the surrounding districts and serving new underground car parks. One of these tunnels runs from west to east directly underneath the Rue Berger [32] (which continues as the Rue Aubry le Boucher as it approaches the Rue Quincampoix and the Pompidou Centre).

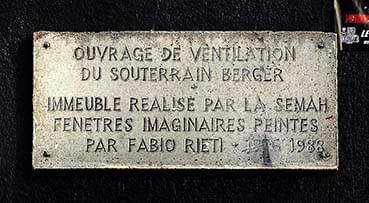

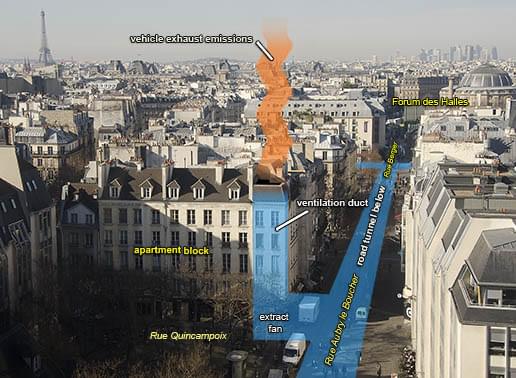

30. [top left] The SEMAH plaque. 31. [top right] New underground access roads beneath the

buildings. 32. [bottom left] Diagram of the relationship between the ventilation duct and the new

underground access roads. 33. [bottom right] A Pompidou Centre car park ventilation duct.

Road tunnels require ventilation in order to maintain adequate air quality, to control spread of smoke in case of fire, and to reduce temperatures to acceptable limits. Exhaust emissions from vehicles need to be removed efficiently so that concentrations of pollutants such as carbon monoxide cannot build up, and this is commonly achieved by installing powerful extract fans in strategic locations, depending on length of tunnel and predicted vehicle usage. It will now be clear that the mysterious structure is a vertical ventilation duct — the plaque on the wall gives us the basic story but is short on details; it can be translated as THE BERGER TUNNEL VENTILATION PROJECT / STRUCTURE EXECUTED BY THE HALLES JOINT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT COMPANY / IMAGINARY WINDOWS PAINTED BY FABIO RIETI 1976 / 1988. We can gather from this that the windows were first painted in 1976, and refreshed twelve years later.

In the interests of deceiving the eye the designers of the duct incorporated window–shaped recesses in the blank wall of the structure so that the ‘imaginary’ painted windows would be framed by realistic shadow lines. Details of the process that led to the decision to treat the duct in this way are not known, and the result contrasts sharply with the uncompromisingly industrial ventilation ducts serving the underground car park of the Pompidou Centre, designed at around the same time [33]. Nor is it known what process led to the commissioning of the artist Fabio Rieti for this project, except that he had been employed a year earlier to decorate the side of a building exposed temporarily during the redevelopment of Les Halles, and this had come about as a result of cooperation with the architects of huge residential complexes in and around Paris — projects in which he was merely asked chose the colours of the wall mosaics. Before that time he had been known as a painter of predominantly urban subjects on canvases of normal size, which he had exhibited in galleries in Italy, America and France. Born in Rome in 1925, he came from an artistic family; his father, Vittorio Rieti, was a composer of ballet scores and this would have brought him and perhaps his son into contact with the ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev, the choreographer Balanchine, and the painter and theatrical designer Giorgio de Chirico — and it is not too far fetched to suggest that there may be echoes of de Chirico’s work in the mural paintings of Fabio Rieti.

When asked in an interview to compare paintings with mural art his reply was centred on the fact that whereas a monetary value can be assigned to paintings, murals — being an ephemeral art and having in his opinion a life of less that ten years — cannot normally be the subject of financial speculation, and equally importantly are applied to an immoveable background and so cannot be exhibited elsewhere. (Note that the French word commonly used for building or structure is immeuble — literally immovable — and that this is the word used on the plaque to indicate the ventilation duct masquerading as a building). He saw mural works of art as having a social role in glorifying the essential nature of the town, and in attracting the eye of the passer–by whose field of vision might otherwise be comparatively empty. He noted, without being specific, that one of his works in Paris had been over–painted by another artist, the result being ‘less strong’; could he have been talking about these particular Beaubourg ‘imaginary windows’?

Fabio Rieti worked throughout his later life with his daughter Leonor, also an accomplished muraliste, restricting himself, on her insistence, to the lower areas of his murals while she worked on the higher scaffolding above — ‘entre ciel et terre’ as he put it.

FALSE WINDOWS: FANCY

The Trompe l’oeil Windows at Biddesden House, Wiltshire, 1711

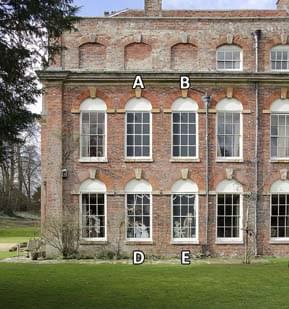

Old houses don’t always give up their secrets easily. The false windows on the east façade of Biddesden House present an intriguing case [34, 35]; those marked C and F coincide with the end of a substantial chimney–stack (not visible in the photograph), and windows A and B clash with a first floor fireplace and a dividing wall — but behind the ground floor windows D and E is a long straight stretch of panelled wall, matching the panelling in the rest of the dining room.

A survey drawing of the floor plans [36] prepared in 1907 at the time of a change of ownership, however, shows a fireplace at this location, blocking off these two windows. A chimney–stack with only two flues would appear to have been built to serve this fireplace together with the fireplace in the bedroom immediately above, hence the blind windows A and B. The stack is in an unusual position, seeming as it does to balance precariously on top of the parapet and looking very much like an afterthought — an addition introduced during the early stages of construction.

34. [left] The east front of Biddesden House showing the blocked windows (note the chimney

stack above). 35. [right] The south and east fronts.

It can be argued from close consideration of the floor plans that there was no need to block up the windows A and B — a fireplace in this first floor bedroom could have been served by the easternmost of the two main stacks located toward the front of the house (which has three chimney pots, only two of which are in use, serving the fireplaces in the two second floor bedrooms above — leaving one pot spare). And it seems clear that the partitioning of the dining room to form a small servery at one end would have blocked off a very grand fireplace at the north end of the room (probably its original location), leaving the dining room itself with no means of heating — and at the same time creating an overheated service room. A photograph in Country Life shows that in 1919 there was then no servery, that the grand fireplace sat at the north end of the room at that time, and that the east, outside, wall was as it is today — a continuous flat stretch of panelling. Most of the floor in the servery area differs from that in the dining room, suggesting that the room had in fact once performed a different function; the current owners remember being told that a fireplace on the east wall of the dining room had definitely existed at some time in the past, which would have been at least up until the time of the survey of 1907. What we might conclude from all this, as well as from the idiosyncratic brickwork detailing mentioned in Note 5, together with the theory put forward that the east, south, and west facades were built at different times — put together in piecemeal fashion and possibly incorporating parts of an earlier structure — is that Biddesden House was not likely to have been designed and built by an architect of national renown, nor that it would have come into being without the close involvement of an owner accustomed to giving orders and having them obeyed. Perhaps it is this circumstance that gives the house its singular quality?

The house in modern times

36. [top left] Floor plans of the south east corner of the house. 37. [top right] The Dora

Carrington window on the west front. 38, 39, 40 [bottom row] The Roland Pym windows A, B, and C.

The Hon. Bryan Guinness, later the 2nd Lord Moyne, bought Biddesden House and dairy farm following his marriage to Diana Mitford in 1929. The house became a centre of cultivated creative society, a country extension of their London lives, and the many visitors included the Sitwells, John Betjeman, Evelyn Waugh, Harold Acton, Lord Berners, Cecil Beaton, Augustus John, the artists Roland Pym and Dora Carrington, and of course the other Mitford sisters. Pamela Mitford ran the Biddesden dairy farm for a time and received two proposals of marriage from John Betjeman. From the Bloomsbury Group, London’s intellectual set, came Lytton Strachey, journalist, biographer and author of Eminent Victorians, a book in which he exposed the hypocrisy of Victorian England; although homosexual, he formed a close and extended relationship with Dora Carrington, painter and former fellow student of Roland Pym’s at the Slade School of Art. Carrington, as she was generally known, painted a trompe l’oeil window [37] on the west side of the later extension to the original house as a surprise for Diana after the birth of her second son Desmond; in it a thoughtful young kitchen maid peels an apple, while the house cat looks longingly at the canary in the cage, forever out of its reach.

Although the early history of the blind windows is not entirely clear we do know that Roland Pym was commissioned by Bryan Guinness to enliven the plain false windows on the east side ground floor of the house. They had met when the painter Robin Darwin had suggested Pym as an illustrator for Bryan’s first children’s book, Johnny and Jemima, Darwin himself having made paintings for the purpose which were rejected by Heinemann’s as being too difficult to reproduce. Pym painted the three ground floor trompe l’oeil windows (D, E, and F), situated on the east façade, in the 1930s [38, 39, 40]. As a theatre designer, landscape artist, book illustrator and muralist his work was very much of the period and was characterised by an elegant romanticism that evoked memories of the faux–Regency creations of the rather better known Rex Whistler. Educated at Eton and the Slade School of Art, Pym enjoyed a career that encompassed set designs for Lohengrin at Covent Garden and Eugene Onegin in Paris as well as murals for some notable clients. He served in the Royal Artillery during the Second World War and later on he illustrated Edith Sitwell’s English Eccentrics, Nancy Mitford’s Pursuit of Love and Love in a Cold Climate, and Thackeray’s Vanity Fair for the Folio Society.

The Biddesden windows are painted in oils directly onto a plastered surface and an unusual feature is that they are covered by glass to protect them from the elements, although when first painted this was not the case; it is recorded that they were restored at least once in their lifetime. They are framed in moulded timber to match the timber surrounds of the adjacent windows, an additional nod in the direction of realism. A horizontal timber member at mid–height mimics the meeting rails of a sash window and casts a realistic shadow.

Perhaps the content of the Pym windows relates to particular episodes in one of Jane Austen’s novels, although it is difficult to be sure of this. The young lady playing the harp could certainly stand for the character in Mansfield Park who most embodies the superficiality of Regency England, the fascinating but morally suspect (for the times) Mary Crawford — “a young woman, pretty, lively, with a harp as elegant as herself, and both placed near a window . . . and opening onto a little lawn . . . was enough to catch any man’s heart”. If we assume for the moment that Mansfield Park was in Pym’s mind when he created these images then the other young women may be intended to portray either Maria Bertram (in love with Henry Crawford, but marries Mr. Rushworth and following their divorce elopes with Henry Crawford), or Julia Bertram (elopes with Mr Yates), or Fanny Price (in love with Edmund Bertram but pursued by Henry Crawford) or less probably Fanny’s younger sister, Susan. This interpretation may be too literal; although Mary Crawford is the only character who actually plays a harp in one of the novels the instrument has its place in portraiture and literature as a symbol of Regency refinement and good breeding. The author of the 1938 Country Life article on Biddesden House expresses the view that ‘here it is surely Mr. Darcy, Catharine Morland, Emma or other beings of Jane Austen’s time whom we surprise in a flirtation, reading a letter, and playing a harp’. The young man might well be any of those mentioned above but we might be safest in saying that he was perhaps simply intended to portray the embodiment of the young Regency male.

Biddesden House is not open to the public, except for two ‘Heritage Open Days’ in September.

Acknowledgements

(All photographs and drawings are by the author unless indicated otherwise)

Picture 1: Wikipedia PD

Pictures 13 — 24: Douglas Colquhoun

Picture 36 based on plans in the Biddesden archive.

The close cooperation and assistance of the owners of Biddesden House is gratefully acknowledged.